Orchid Hunter in the Lab: The Role of Mycorrhizae

Orchid hunters have long known that where resurrection ferns are found, so are orchids. Student orchid hunters are looking for the reasons why—and they’ve started with shared mycorrhizae.

“If you’re looking for epiphytic orchids in South Florida,” shared the orchid hunter, “look for resurrection ferns first. They’re easier to find and they usually grow with orchids.”

For decades, this trade secret was merely anecdotal advice among those who spent countless hours searching for South Florida’s rare orchid jewels. Today, however, five 11th graders from Fairchild’s own BioTECH @ Richmond Heights 9-12 botany magnet high school are testing why orchids and ferns tend to cohabitate.

This work began last summer, when Fairchild’s summer high school interns put the orchid hunter’s advice to the test in the lab. They wondered whether resurrection ferns might share the same mycorrhizal as some Florida orchids.

In Greek, “myco” means fungus and “rhiza” means root. In English, root-fungus or “mycorrhizae” are symbiotic relationships between plants and fungi, beginning at the roots. Although nobody knows for sure how many organisms benefit from these relationships, certainly a large majority of all plants on earth are included among the beneficiaries.

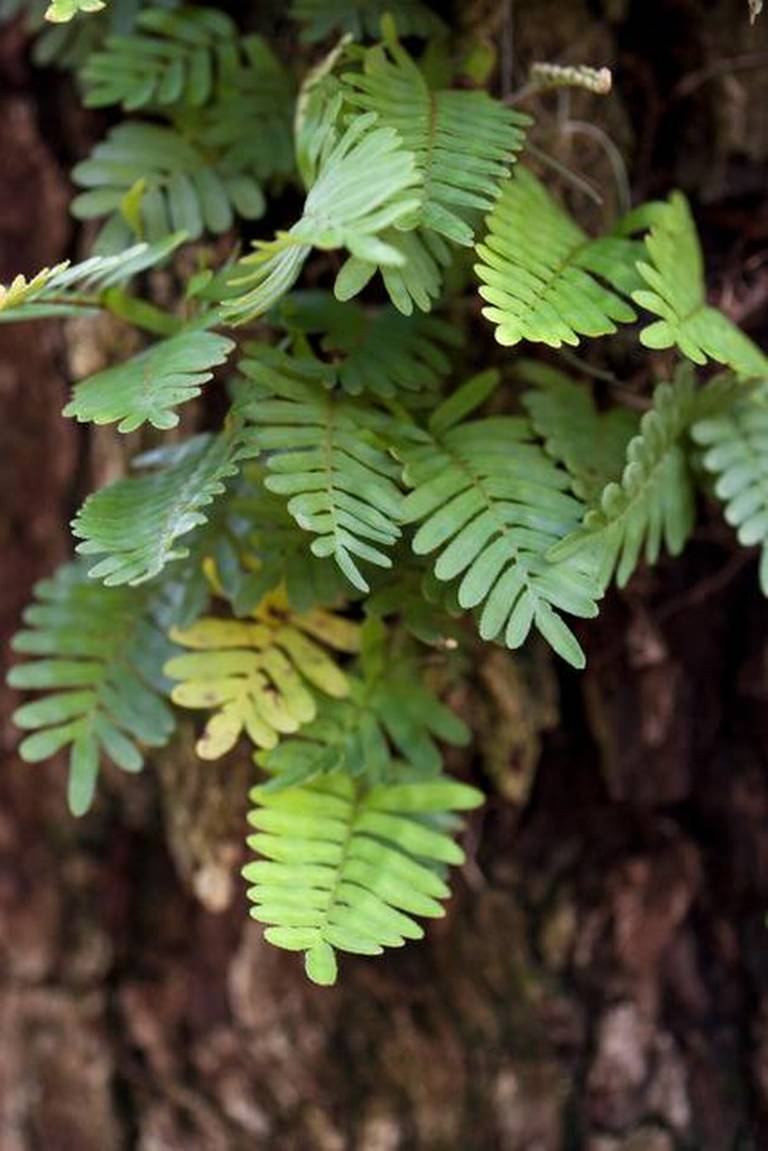

Under the guidance of Fairchild Orchid Biologist Dr. Jason Downing, the BioTECH interns discovered that the resurrection fern (Pleopeltis polypodioides) and the Florida butterfly orchid (Encyclia tampensis) indeed share the same species of mycorrhizal fungi. This discovery brings scientific evidence and an explanation to the orchid hunters’ adage, and opens the door to countless research questions about species connected via mycorrhizae. Now, 11th grade BioTECH students are expanding on the interns’ research, and have added a few questions of their own.

“We’re studying the ecological relationship between ferns and orchids and the role of the mycorrhizal fungi shared between them,” explains Caro V., a BioTECH 11th grade research student. The team of students is exploring which ferns and orchids might share fungi and whether the compositions between different combinations of orchids and ferns are the same. Previous studies suggest that orchids and ferns utilize fungi independent of each other. This study, however, builds upon and improves what we currently know about the relationship and asks new questions. Thanks to the summer intern study, we now have evidence that the butterfly orchid and the resurrection fern share a fungus. Maybe other species do too. “This study documents new relationships between mycorrhizal fungi and different plant species,” Downing explains. “The findings could change the way we think about plant/mycorrhizae interactions and biodiversity on a global level.”

Because their relationship is symbiotic, both the fungus and host plant benefit from it. The fungus colonizes the roots of the host plant and extends its hyphae—fungal filaments—many feet beyond the extent of the roots. The hyphae collect nutrients and water and share them with the host plant, greatly increasing the host plant’s access to vital ingredients. The fungus, in return, receives sugars from the plant’s photosynthetic process. Thanks to this relationship, both organisms are healthier, stronger and better-suited to survive. Given the proliferation of mycorrhizae in plant communities throughout the world, ecological systems are therefore healthier, stronger and better-suited to survive.

As with many plant science research projects, the mycorrhizae study process begins in the field. BioTECH students collect root samples throughout the Garden and neighboring public and private lands—including overlaying orchid and fern roots

of different species. Orchid and fern roots that physically overlap in their natural setting are more likely to share fungi, so collecting them increases our ability to identify a shared fungal species. Back in Fairchild’s Baddour DNA lab, students “surface sterilize” the samples to ensure the DNA collected originates from the inside of the sample and not the outside. DNA on the surface could potentially represent a different organism living in proximity, thereby disrupting the results. After extracting the DNA, students sequence for fungal DNA using fungi-specific primers, thus identifying the shared fungi.

Although the extracting and sequencing processes are standard throughout the plant research world, the application is cutting-edge, and our BioTECH students are holding the tools. Today’s research by tomorrow’s plant scientists sheds light on both the plants and the classroom. Our collective understanding of the infinitely complex web of plant/fungi relationships continues to grow with every discovery and, as one BioTECH student said, “There’s no reason to stop.” In the meantime, the orchid hunter will continue looking for ferns first and the BioTECH students will continue asking, “Why?”

This article was authored by Thaddeus Foote and originally appeared in the Spring 2017 edition of The Tropical Garden. Minor changes from the print version of this article were introduced to improve readability in a digital format.