The Mysteries of Mangifera: Finding the Mango’s Origin

We think we know our mangos, but much of their origin is a mystery researchers are trying to unravel through exploration, DNA research and other methods. They’ve even begun to ask if all cultivars of this incredibly diverse fruit are truly the same species.

In South Florida, we know our mangos. During our sultry summers, they seem to drip off the trees scattered throughout our neighborhoods. Those of us who stick out the steamy weather are lucky enough to experience the amazing diversity of mango size, shape, color, texture and, best of all, flavor.

Yet the mango cultivars that we know and love—from the blushing ‘Haden,’ to the glowing ‘Nam Doc Mai,’ to the rich ‘Alphonso’—represent only a small part of a large and somewhat mysterious genus of plants that are unique, diverse and important in their own right, but are little-known outside of their homeland in Asia.

The mango belongs to the genus Mangifera, which contains approximately 69 species in total, and is part of the poison ivy family, Anacardiaceae (this explains why some people develop contact dermatitis from mango sap). Mangifera species are native to South and Southeast Asia, with a range spanning from India eastward to the Solomon Islands. While the heart of Mangifera diversity lies in the wet, tropical lowland forests of Borneo, Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, some species can grow in very different environments, including savannahs, mangrove swamps and elevations over 3,200 feet. All 69 Mangifera species are trees, and most grow to be quite tall, reaching 120 feet or greater, with long, straight trunks that are valued for timber.

Like many tropical tree species, Mangifera do not grow in dense stands, but are very sparsely scattered throughout the forest, and individual trees typically do not flower every year. The combination of the height of Mangifera trees, their low density in tropical forests and their sporadic flowering makes it difficult to locate, identify, study and collect Mangifera in the wild. This is one of the primary reasons why there remains some uncertainty about how many species of Mangifera exist.

While few wild Mangifera species produce fruits that are as delectable as mango, local peoples in South and Southeast Asia consume fruits from some 26 other species of Mangifera. Some, like Mangifera foetida, or horse mango, are cultivated in the home gardens, or kampongs, of villagers in Malaysia and Indonesia. The unripe fruits of M. foetida and many other Mangifera species are frequently used to make sambal, a spicy, pickled dish.

We humans are not the only ones who love to eat Mangifera fruits—in the wild, they are a favorite of such iconic megafauna as hornbills, orangutans, rhinos and elephants. With the disappearance of these important seed dispersers and the forests themselves, many Mangifera species are in danger of vanishing. Unfortunately, less than half of Mangifera species are currently preserved in ex-situ collections like botanic gardens, and only about a dozen species are growing outside of Asia.

Exploring for Wild Mangifera – In the Field and in the Lab

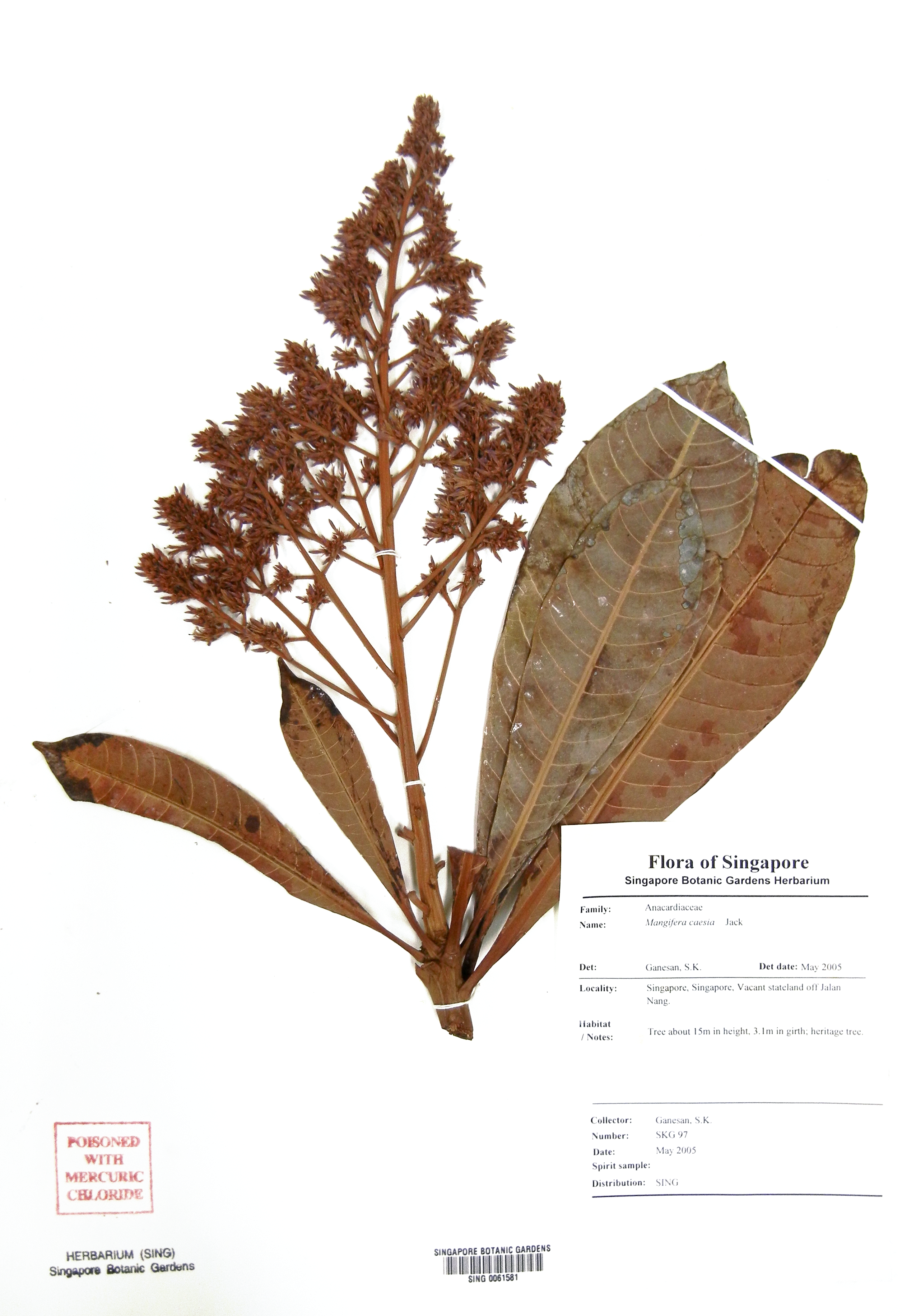

Although Mangifera species can provide valuable context for scientific studies focused on cultivated mango, few, if any, wild species are typically included in such research due to their poor representation in herbarium and living collections. As a Ph.D. student at Florida International University, I set out to catalog the diversity of this important genus of plants, and to use wild Mangifera species to provide a broader understanding of the history of the mango itself.

For my research, I visited herbaria, botanic gardens and forest research plots in Singapore (Singapore Botanic Gardens, Gardens by the Bay), Malaysia (Pasoh Forest Reserve, the Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Sandakan Herbarium), Indonesia (Bogor Botanical Gardens, Purwodadi Botanical Garden) and the United States (Miami-Dade’s Fruit & Spice Park, the USDA’s Chapman Field Subtropical Horticulture Research Station and Fairchild) to study and collect samples from as many Mangifera species as I could find.

By working closely with collections abroad, I experienced firsthand how difficult it is to determine whether individuals are from the same species or not just by looking at them. It is particularly tough in plants—individuals of the same species can look very different depending on their stage of life (seedling vs. sapling vs. mature tree), or growing conditions (sun/shade or nutrient availability), and it is often impossible to definitively identify a species without looking at its flowers, which are not always available. For these reasons, I used DNA sequencing to help decide which individuals belong to the same species and which represent different species.

I also used DNA sequences to learn about how different Mangifera species are related to one another. I then applied the knowledge of these relationships in different ways. For example, since many species in the genus are cultivated for their fruit, you might assume that these species are closely related to one another, while species that produce unpalatable fruits are more distantly related. However, my analysis shows that this is not the case; species that are cultivated for fruit are scattered throughout the genus. Similarly, I can investigate fruit color, adaptations to different environments and many other characteristics.

Understanding the relationships between Mangifera species also has direct applications to mango breeding and cultivation. Mango is most likely to be able to interbreed with its closest relatives, and these species could therefore be used in breeding programs to introduce important traits like disease resistance. In addition, mango growers can use closely related species as rootstocks for mango, which may allow mango to be grown in different soil conditions or possibly even produce a dwarf mango tree.

Get Info About the 2025 Mango Festival at Fairchild in Miami!

Teasing Out the Mango’s True History, and Why Some Mangos May Not Actually be Mangos

Finally, understanding how mango is related to other species of Mangifera provides critical insight into where and how the mango was domesticated. The traditional story of the mango goes something like this: the mango is a single species, Mangifera indica, that grows wild in the foothills of the Himalayas, was domesticated in India around 4,000 years ago and was introduced first into Southeast Asia before being transported along trade routes to the rest of the world’s tropics and warm subtropics. This storyline is supported by linguistic and archaeological evidence, but is certainly not infallible. In fact, it is entirely possible that some mangos are not mangos at all.

Most mango enthusiasts know that mango cultivars can be separated into two main categories: Indian types and Southeast Asian types. These cultivar types produce fruits that differ in appearance and flavor. Indian types tend to have more orange-red coloration when ripe, are more oval in shape and have a strong flavor. Southeast Asian types usually turn yellow or stay green upon ripening, are flattened with a pronounced “nose” or paisley shape and have a mild flavor. Another key difference is that Indian cultivars are generally monoembryonic, meaning they produce a single embryo in each seed, whereas Southeast Asian cultivars are often polyembryonic, and produce multiple embryos in a single seed.

In addition to the differences in fruit traits, recent studies of DNA sequences from mango cultivars, including my own analysis, indicate that Southeast Asian and Indian mangos are also genetically distinct from one another. However, the conventional historical account of the mango fails to explain the presence of two such distinct types of mango cultivars.

So, what can explain this tale of two mangos? Pinpointing a cause for the divergence between Indian and Southeast Asian mangos is difficult, but there are a few likely scenarios that primarily involve three key variables: the number of domestication events, the order/location of the domestication events and the number of species involved. The likely scenarios:

1. One species, a single Southeast Asian domestication

It may be that the mango was first domesticated in Southeast Asia from a single wild species, and was later introduced into India, where it was cultivated intensively and improved. The initial domestication event in Southeast Asia would have produced early Southeast Asian cultivars, and further cultivation and selection for different traits in India could have produced a secondary population. While wild M. indica is not thought to occur in Southeast Asia, it is possible that the wild populations from that region have disappeared over time. However, based on genetic analysis of mango, this scenario does not seem likely.

2. One species, two domestications

Mango may have been domesticated from the same wild species, M. indica, independently in India and Southeast Asia. Wild mango may have had a rather broad range, with genetically distinct populations in both India and Southeast Asia. If domestication happened in both locations independently, it could explain the differences we see in mango cultivars.

3. Multiple species, one Indian domestication

Of course, the presence of two different cultivar types does not preclude India from being the origin of domestication of the mango. It is possible that mango was domesticated from a single wild species in India, and upon introduction to Southeast Asia, the center of diversity of mango’s wild relatives, cultivated M. indica hybridized with one or more of these wild Mangifera species, producing a unique set of cultivars. This would not be much of a surprise, as many tree crops, including apple and most citrus fruits, are the result of hybridization between two species.

4. Two species, two domestication events

Finally—and let me warn you, the very suggestion of this is controversial—there is a possibility that some mangos are not mangos at all. Within the Mangifera genus, there are a few species that very closely resemble mango. It is entirely possible that the mango we think we know is, in fact, the descendent of two distinct, closely related species that were domesticated in India and Southeast Asia separately. Although Indian and Southeast Asian cultivars can interbreed, this is not unusual for closely related tree species. While the idea that mango is two distinct species may seem unbelievable, botanists have proposed it in the past as a way to reconcile the two distinct cultivar types, and recent genetic analysis indicates it could actually be the correct answer.

A great deal of work still needs to be done in order to arrive at a more definitive answer as to which of these scenarios is the most likely explanation for the differences observed between Southeast Asian and Indian mangos.

Surprisingly, one of the most important gaps in our knowledge about the mango is because it is difficult to say exactly where, or even whether, wild populations of M. indica still exist. Historically, botanists claimed that truly wild M. indica were found in the valleys of Northeastern India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and Northern Myanmar. However, deforestation in these regions has been heavy, and it is difficult to acquire access to these areas as a foreign researcher. I have spoken with scientists from around the world, and not one of them has been able to tell me they have seen wild M. indica with their own eyes. These elusive populations of wild mango could hold the key to understanding the domestication of this fruit.

For now, though, we can only revel in the mysteries of Mangifera’s diversity—after all, who doesn’t love a good mystery?

This article was written by Emily Warschefsky and originally published in the Summer 2017 issue of the Tropical Garden. Minor changes from the print version of this article were introduced to improve readability in a digital format.