Perhaps no other plant provokes such strong emotions as the orchid. People go to great lengths — some legal, some not — to possess them, with often disastrous results for wild populations.

Although orchids grow throughout the United States, we are lucky in Florida to foster some of the most beautiful, showy and rare examples. Starting in the late 19th century, however, we began loving them to death.

Collectors and plant lovers reaching South Florida tore orchids by the wagonload from live oaks, pond apples, cypress and anywhere else they could reach. They were shipped to buyers looking for pretty, exotic houseplants.

Natives to the sub-tropics, the orchids were not likely to survive for long in a cold, dry city dwelling. So being plentiful and inexpensive, they were simply thrown away when the flowers faded.

Eventually the seemingly endless supply began to run out, so that nowadays you might be hard pressed to find many native orchids in the wild. Habitat destruction for agriculture and housing and cypress logging only compounded the dire situation of our orchids.

Sadly, their scarcity today makes them a target for poachers who sell the now-rare plants at high prices. Consequently, finding wild native orchids is nearly a thing of the past. Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden wants to change that as part of our mission to conserve the world of tropical plants. Fairchild is dedicated to reintroducing species of our native orchids by propagating them in our lab.

In Bloom: Flowers of the butterfly orchid. Kenneth Setzer/FTBG.

Carl Lewis, Fairchild’s director, explains why these orchids are not likely to recover on their own: “In the natural process, an orchid produces a seed pod containing thousands of tiny seeds, as small as grains of sand; when the pod opens, the seeds are meant to be carried by the wind to suitable locations for them to germinate.

“An orchid seed’s journey on the wind must take it to the perfect location, lodging it on a suitable host tree. The lighting, humidity and temperature must be ideal. They also need to form a symbiotic relationship with a specific fungus to provide the necessary energy to germinate.”

However, by growing orchid seeds under idealized laboratory conditions, each seed pod can be nearly guaranteed to produce thousands of offspring.

Thriving at Fairchild: Orchid seedlings grow in the laboratory. Kenneth Setzer/FTBG.

“Scientists at Singapore Botanic Gardens have been propagating several native orchid species for several decades,” Lewis relates. “They’ve re-established orchids on trees in urban areas. It’s been so successful that they are now reproducing naturally on trees in downtown areas in Singapore.

“We are aiming to reintroduce propagated native orchids in urban and suburban areas in South Florida, starting with the butterfly orchid, Encyclia tampensis and the cowhorn orchid, Cyrtopodium punctatum, both of which grow at Fairchild. Our goal is to produce one million orchids in five years’ time to be reintroduced onto suitable trees in these areas.”

Growing a million orchids in five years seems mind boggling, but it adds up: One seed pod can produce approximately 12,500 seeds. The Fairchild lab harvests about 16 seed pods a year, which will generate a million plants in five years.

Orchid seed pod opened to reveal seeds. FTBG volunteer department.

Harvesting and growing the dust-like seeds is no easy task. Susie Lau and Julie Berlin, volunteers in Fairchild’s Micropropagation Lab, know this well. They and other volunteers in the Paul and Swanee DiMare Science Village’s Jane Hsiao Laboratories have been trained in laboratory procedures and micropropagation, and are attentive to painstaking detail.

First, the orchid seed pod exterior is sterilized to ensure no bacteria, mold, or fungi are introduced that might contaminate and destroy the seeds.

Following a very specific recipe, the volunteers mix the growing medium and pour it into sterile glass bottles.

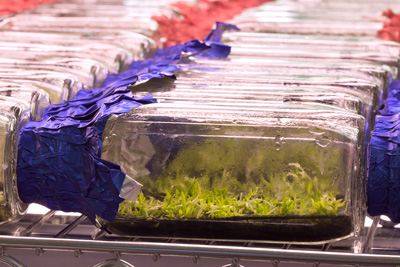

The seed pod is carefully opened with a scalpel, exposing the seeds, which can then be sown in a bottle. Each bottle is sealed with a foil wrapper, colored to indicate when the seeds were sown, and placed on racks under grow lights.

“It takes about three to four months to actually see something green start to grow inside the bottles,” Berlin says.

Every two to four months thereafter, as the tiny grass-like seedlings fill their containers, they need to be gently but quickly removed with a forceps and transferred to a different bottle. The transfer is performed in a sterile cabinet to ensure that nothing contaminates the process.

Step by step in the lab: Orchid seedlings are put into a larger bottle under sterile conditions. Kenneth Setzer/FTBG.

The lab has about 150,000 individual orchids at different stages of development growing in 1,200 bottles.

“From seeding to the time they can live out of the bottle depends on the species, but it takes about 18 months,” Lau said. Just recently, the first seedlings to outgrow their bottles were removed and taken to Fairchild’s nursery to continue maturing, she said.

The project is yielding more than rare plants: Fairchild researchers are taking the opportunity to study under what conditions our native orchids grow best, including variables like different growing media and types of lighting. This research will further benefit future conservation, including Fairchild’s plans to restore populations of the native dollar orchid (Prosthechea boothiana) and cockleshell orchid (Prosthechea cochleata).

Bottle containing orchid seedlings growing in Fairchild's Jane Hsiao Laboratories. Kenneth Setzer/FTBG.

Since these orchids eventually will be transplanted into public places, engaging the local community is an important aspect of the program. Last October high school students at Terra Environmental Research Institute in Miami received a visit from Fairchild staff, along with a delivery of stainless steel racks, lighting and bottles containing butterfly orchid and cowhorn orchid seedlings. Their task is to raise them, monitoring the ideal amount of light exposure required for healthiest growth.

These students are getting hands-on experience in what it takes to conserve and restore a community of plants. Appropriately, many of these orchids will ultimately be attached to host trees at this and other local schools.

“At about six to nine months after leaving the bottles, the orchids can go back into trees they would naturally inhabit,” Lewis says. “We are partnering with local South Florida communities, schools and municipalities to get the orchids into trees in urban and suburban areas. The community will play a large part in the reintroduction.”

Researchers hope that growing these orchids in populated areas will support wild populations by providing a source of genetic diversity, as well as supporting the bees and other pollinators these plants will need to reproduce naturally.

It’s not too late to restore some of our most vulnerable plants, one million orchids at a time.

To learn more and become a supporter of the Million Orchid Campaign, visit: www.fairchildgarden.org/The-Million-Orchid-Campaign/ or attend Fairchild’s Orchid Festival, March 7-9.